You step into a cool, dim cellar—Stored Food Before Refrigerators in action—as apples perfume the room, potatoes rustle in burlap, and jars glint on rough-cut shelves.

Resource pick: Want a ready list of shelf-stable, no-fridge foods with modern, safe methods? Check out the Lost Superfoods pantry guide.

This is Stored Food Before Refrigerators in practice—pre-refrigeration food storage powered by root cellars, icehouses, evaporative cooling, drying and smoking, salting and brining, vinegar pickling, lacto-fermentation, sugar preserves, and tight grain storage.

Here, you’ll learn how people stored food before refrigerators—and how to store food without a fridge safely using today’s tested steps (correct acidity, salinity, time/temperature, and processing).

You’ll leave with small, doable projects to master Stored Food Before Refrigerators: build a simple root bin, pack bright pickles, start a reliable ferment, and put up shelf-friendly preserves for an off-grid-ready pantry.

Read This First: Safety, Scope, and Smart Adaptations

You’re here for old skills, not old risks. Learn how people Stored Food Before Refrigerators—then apply tested, modern methods so pre-refrigeration food storage stays safe today.

-

Acidity: High-acid foods (≈ pH ≤ 4.6) can be safely water-bath canned with tested recipes. Low-acid foods (most vegetables and all meats) require pressure canning for shelf stability.

-

Water activity: Drying, salting, and sugaring work by reducing available water; containers and humidity matter.

-

Temperature: Cool, dark, steady environments slow spoilage; heat speeds it up.

-

Cleanliness: Clean tools, intact containers, correct headspace, proper seals.

-

Altitude: Increase water-bath times and adjust pressure as elevation rises.

-

Bottom line: Follow tested recipes for anything shelf-stable. Tweak flavor, not safety.

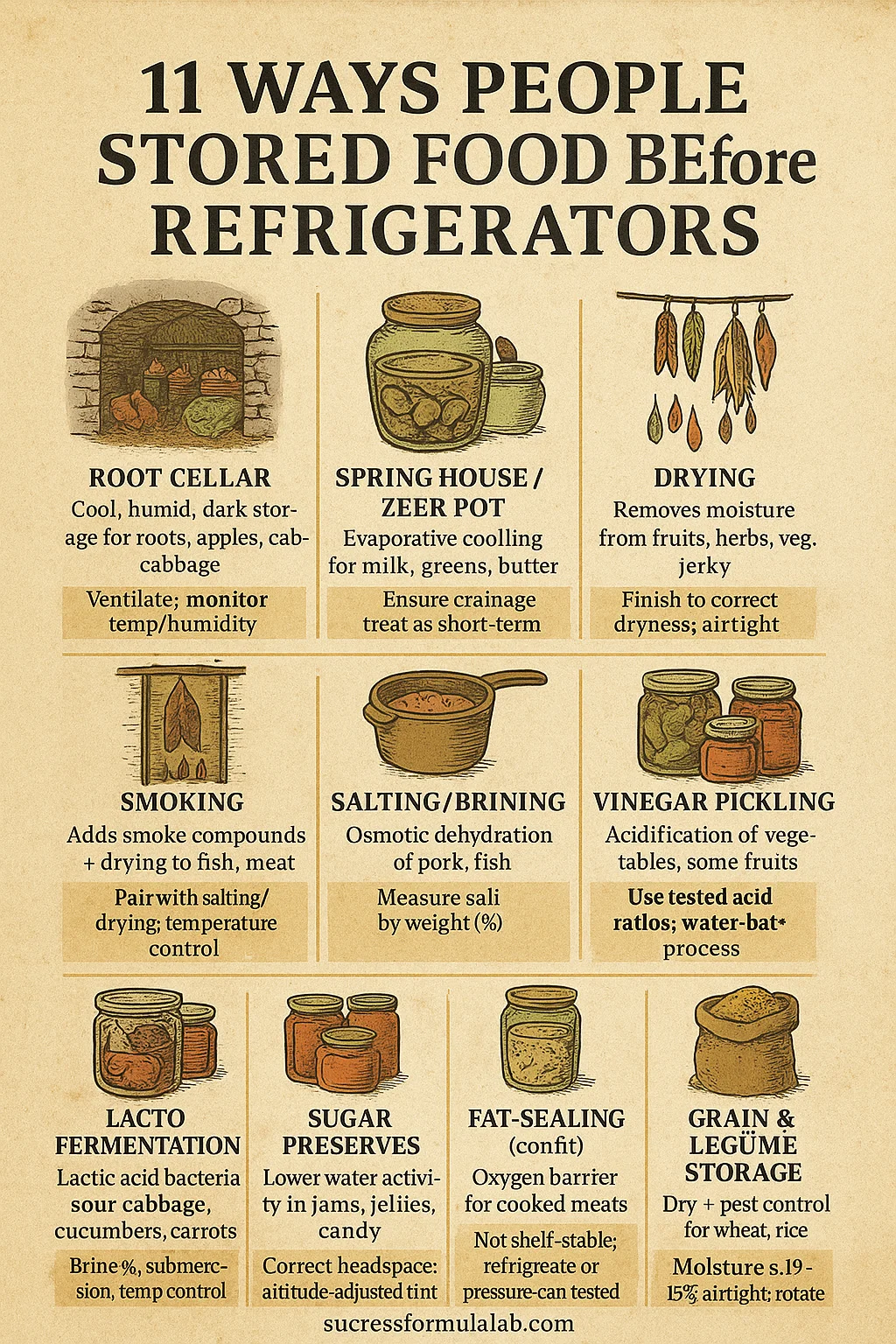

Snapshot: Methods at a Glance

| Method | Best For | Core Principle | When to Choose It | Modern Safety Pointer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root cellar / cool pantry | Roots, apples, cabbage | Cool, humid, dark | Seasonal storage without processing | Ventilate; monitor temp/humidity |

| Icehouse / stored ice | Dairy, meats (short term) | Ice + insulation | Temporary chilling | Ensure drainage; treat as short-term |

| Spring house / zeer pot | Milk, greens, butter | Evaporation / cool water | Low-energy cooling | Works best in dry air + shade |

| Drying / dehydrating | Fruits, herbs, veg, jerky | Remove moisture | Lightweight, compact | Finish to correct dryness; airtight |

| Smoking (hot/cold) | Fish, meat | Smoke compounds + drying | Flavor + preservation | Pair with salting/drying; temperature control |

| Salting / brining | Pork, fish | Osmotic dehydration | Historic proteins | Measure salt by weight (%) |

| Vinegar pickling | Vegetables, some fruits | Acidification | Fast pantry sides | Use tested acid ratios; water-bath process |

| Lacto-fermentation | Cabbage, cucumbers, carrots | Lactic acid bacteria | No-vinegar sour | Brine %, submersion, temp control |

| Sugar preservation | Jams, jellies, candy | Lower water activity | Fruit spreads | Correct headspace; altitude-adjusted time |

| Fat-sealing (confit, potted) | Cooked meats | Oxygen barrier | Flavorful, short-term | Not shelf-stable; refrigerate or pressure-can tested recipe |

| Grain/legume storage | Wheat, rice, beans | Dry + pest control | Long-term basics | Moisture ≤ ~12–13%; airtight; rotate |

1) Root Cellars and Cool Pantries

How it works

Earth behaves like a thermal battery. A cellar tucked into a hillside or under a house holds steady cool temperatures and high humidity, ideal for crisp roots and storage apples. Darkness discourages sprouting and greening.

What to store

Potatoes (unwashed), carrots and beets (in damp sand), rutabaga, turnips, cabbage (hung), apples (wrapped or spaced), winter squash (drier shelf).

How to do it today

-

Target 32–40°F (0–4°C) for most roots; 90–95% humidity keeps them from shriveling.

-

Provide ventilation (cool air low, warm air high) and separate zones: drier for onions/garlic; more humid for carrots/beets.

-

Inspect weekly and remove anything soft, sprouting, or moldy.

Watch-outs

Ethylene from apples can hasten sprouting in potatoes—store apart.

2) Icehouses and Harvested Ice

How it works

Blocks of winter ice insulated with sawdust kept pantries and iceboxes cool for weeks.

How to do it today

For outages, camping, or butchering days, rely on well-insulated coolers. Keep meltwater draining, and treat ice storage as short-term only.

Watch-outs

Standing water warms food and invites microbes; drain it.

3) Spring Houses and Zeer Pots

How it works

A spring house sits over flowing water; a zeer pot (unglazed clay nested in clay with wet sand between) cools by evaporation. Shade + airflow improve the effect.

How to do it today

In dry climates, keep the outer pot damp and place it where air moves but sun doesn’t hit directly. Expect days to a week of extra life for tender greens and dairy—not months.

Watch-outs

High humidity reduces evaporative cooling; results vary by climate.

4) Drying and Dehydrating

How it works

Drying lowers water activity so microbes can’t multiply—one of the core Stored Food Before Refrigerators methods. Fruits, herbs, vegetables, and meats can be safely dried to target textures and then sealed.

How to do it today

-

Fruits/veg/herbs: Dehydrator or low oven; thin, even slices; rotate trays.

-

Jerky/meat: Use a proven pre-heat step and dry to dry, pliable—no wet spots.

-

Storage: Cool, dark, airtight. Desiccant packets help in humid regions.

Watch-outs

In humid climates, sun-drying is unreliable; choose a dehydrator.

5) Smoking (Hot vs. Cold)

How it works

Smoke contributes antimicrobial compounds and drying. Hot smoking cooks; cold smoking requires pairing with salting/drying plus strict temperature control.

How to do it today

Salt first for safety, keep temperatures in the correct range, and combine with drying for longer storage. If not fully preserved, treat smoked food as refrigerated.

Watch-outs

Cold-smoking hazards rise if temps climb; know your smoker.

6) Salting and Brining

How it works

Salt draws out moisture and inhibits spoilage. Classic staples—salt pork, salt cod—lasted through winters and sea voyages.

How to do it today

Measure salt by weight (not spoons). Keep meat fully submerged. After storage, soak to desalinate before cooking.

Ingredients-First Table: Basic Salt Pork Brine

| Recipe | Container | Ingredients & Amounts | Target Salt % | Method | Time | Yield | Storage Tips |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salt Pork (basic brine) | Crock / food-safe bin | Water; 10–15% salt by weight; optional sugar & spices | 10–15% | Submerge fully; weight to keep under brine | Days–weeks | Varies | Cool, dark; desalinate before cooking |

Watch-outs

If you want room-temp, long-term meat today, use tested pressure-canning recipes instead.

Mid-Content Pantry Boost

If you want a ready-to-follow companion that turns these historic methods into modern, shelf-stable projects, explore the Lost Superfoods pantry guide. It focuses on historically inspired no-fridge foods (think dried and salted proteins, portable soup, fat rendering, dry mixes, and more) adapted to today’s safety steps—handy when you’re building an off-grid-ready pantry.

7) Vinegar Pickling

How it works

Vinegar lowers pH; with a tested acid ratio and a boiling-water canner, vegetables become bright, shelf-stable sides.

How to do it today

Use 5% acidity vinegar (unless a tested recipe specifies otherwise). Don’t dilute beyond recipe specs. Respect headspace and altitude adjustments.

Ingredients-First Table: Quick Pickled Carrots

| Recipe | Jar Size | Ingredients & Amounts | Headspace | Method | Time* | Yield | Storage Tips |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quick Pickled Carrots | Pint | Carrots; 1:1 vinegar:water (5% vinegar); 2% salt by weight; spices | ½ in | Boiling-water canning | 10 min baseline* | ~4 pints | Cool, dark; best within 1 year |

*Increase water-bath time per altitude tables.

Watch-outs

Soft pickles usually come from weak brine, diluted vinegar, or overcooking.

8) Lacto-Fermentation

How it works

Salt and time let lactic acid bacteria acidify vegetables. No vinegar needed—flavor develops naturally.

How to do it today

-

Use 2% salt (20 g per 1 kg veg) for cabbage; 2–3% works for many other veg.

-

Keep everything submerged and ferment around 60–72°F (15–22°C).

-

When sour enough, refrigerate or follow a tested canning method.

Ingredients-First Table: Basic Sauerkraut

| Recipe | Jar Size | Ingredients & Amounts | Brine/Salinity | Method | Time | Yield | Storage Tips |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sauerkraut (basic) | Quart / Liter | Shredded cabbage; 2% salt | Self-brining | Pack firmly, keep submerged; ferment at ~68°F | 1–4 weeks | ~1 qt per ~1.5 lb cabbage | Refrigerate when sour enough; optional tested canning after |

Watch-outs

Scum or mold indicates exposure to air. Keep veg submerged with a weight and maintain good hygiene.

9) Sugar Preservation (Jams, Jellies, Candied Fruit)

How it works

High sugar ties up water; paired with proper acidity and a boiling-water process, fruit spreads keep beautifully.

How to do it today

Use bottled lemon juice when a recipe calls for it (consistent acidity). Respect ¼-inch headspace for jams. Adjust times for altitude. For clear gels, cook in a wide pan and follow pectin directions precisely if used.

Watch-outs

Old open-kettle methods (no processing) invite mold. Always water-bath can tested recipes.

10) Fat-Sealing (Confit, Potted Meats)

How it works

Historically, cooked meat was stored under a solid cap of fat to exclude oxygen in a cool cellar.

How to do it today

Enjoy confit as a refrigerated delicacy. For shelf-stable meat, use tested pressure-canning recipes specific to the cut.

Watch-outs

Room-temperature storage of fat-sealed meats isn’t considered safe by modern standards.

11) Grain, Legume, and Seed Storage

How it works

Grains and beans last when they’re dry, cool, dark, and pest-free. Moisture below ~12–13% is the rule of thumb.

How to do it today

Use airtight containers (food-grade buckets with gasket lids, mylar liners, or glass). Consider diatomaceous earth for pests or appropriate oxygen control used correctly and in the right container. Label clearly and rotate (FIFO).

Watch-outs

Warm, humid storage invites bugs and rancidity. Keep containers off concrete floors and out of sunlight.

Skills You’ll Reuse Across Methods

Planning and rotation

Map your pantry. Date everything. Build a FIFO habit so older items move forward. A quarterly “pantry audit” saves more food than any single preservation trick.

Measure, don’t guess

Weigh salt for brines and ferments. Use a thermometer for jerky pre-heats and jam gel points. Check cellar temperature/humidity with simple gauges. Use pH strips or a meter when a recipe requires confirmation.

Adapt tradition with modern assurance

Stick to tested recipes for shelf-stable foods. Customize flavor (herbs, spices) without changing safety-critical ratios.

Troubleshooting and Common Mistakes

-

Soft pickles: Brine too weak, vinegar diluted, or overcooked. Use a tested ratio and avoid boiling jars to death.

-

Ferment going funky: Too little salt, too warm, or veg not submerged. Adjust salt %, cool it down, keep everything under brine.

-

Jerky too chewy or risky: Uneven slicing, no pre-heat, under-dried. Slice thinner, follow the pre-heat step, dry to the correct finish, then store airtight.

-

Moldy jam under wax: Skip paraffin. Use two-piece lids and a proper water-bath process.

-

Cellar rot or sprouting: Temperature or humidity off; improve ventilation, separate ethylene producers, remove compromised produce fast.

-

Pest-bitten grain: Not airtight or too moist; move to sealed containers, add pest barriers, and keep cool.

FAQs About Stored Food Before Refrigerators

Here’s a refreshed, SEO-friendly FAQ you can drop into your article. I’ve woven the exact phrase Stored Food Before Refrigerators where it fits naturally and kept answers concise, practical, and safety-first.

1) What does “Stored Food Before Refrigerators” actually mean today?

It refers to pre-electric methods—root cellars, drying, smoking, salting, pickling, fermenting, ice storage, and careful grain keeping. You can still use many of these with modern safety tweaks (tested recipes, measured brines, correct processing times).

2) How did people store meat before refrigerators—and what’s safest now?

Historically: salting, smoking, drying, and fat-sealing (confit) in cool cellars. Today, if you want meat shelf-stable at room temperature, use tested pressure-canning recipes. Otherwise, refrigerate or freeze.

3) Are root cellars still useful, and what should you store in them?

Yes—if you can maintain cool (≈32–50°F/0–10°C), dark, and humid conditions. Store potatoes (unwashed), carrots/beets (in damp sand), cabbage, apples (separate from potatoes), and winter squash (on drier shelves). Inspect weekly.

4) How did households manage dairy when they Stored Food Before Refrigerators?

Short term, they chilled with icehouses, spring houses, or evaporative coolers (zeer pots). Treat these as temporary cooling; for long storage, use modern refrigeration or convert dairy into longer-keeping products (e.g., hard cheeses) with safe methods.

5) What’s the difference between vinegar pickling and lacto-fermentation?

Pickling uses vinegar for predictable acidity and can be water-bath canned with tested ratios. Lacto-fermentation uses salt + time to create lactic acid; you must keep vegetables submerged, control temperature, and then refrigerate or process per a tested method.

6) What brine strength should you use for fermentation?

As a rule of thumb: ~2% salt by weight for cabbage (20 g per 1 kg), and 2–3% for many other vegetables. Keep produce fully submerged and ferment cool (about 60–72°F / 15–22°C).

7) Can you safely store cooked meats under fat (confit) at room temperature?

No by modern standards. Enjoy confit refrigerated, or choose a tested pressure-canned recipe if you need shelf stability.

8) How dry is “dry enough” for dehydrated foods?

Fruits: leathery/pliable with no beads of moisture. Herbs: brittle. Jerky: dry, flexible, no wet spots. Cool completely, then store airtight in a dark, cool place; consider a desiccant in humid climates.

9) How did people keep food cool in hot climates without electricity?

They used shade, airflow, evaporative cooling (zeer pots), and nighttime venting. Expect days to a week of benefit—not months. Pair with fast methods like pickling or drying.

10) How should you store grains and legumes long term?

Keep them dry (≤~12–13% moisture), cool, dark, and pest-proof. Use airtight containers (gasket buckets, mylar liners, or glass), label dates, and rotate (FIFO). Consider diatomaceous earth or proper oxygen control where appropriate.

11) What shelf life should you expect from these methods?

Unsealed or bulging lids, off smells, visible mold (aside from harmless surface yeasts on ferments), slimy textures, or fizzing where it shouldn’t are classic spoilage signs in Stored Food Before Refrigerators methods. When in doubt, discard.

12) What are the red flags of spoilage?

Unsealed or bulging lids, off smells, visible mold (except harmless surface yeasts on ferments you can safely remove when appropriate), slimy textures, or fizzing where it shouldn’t. When in doubt, discard.

13) How do altitude adjustments affect canning times?

Higher elevations require longer water-bath times and/or different pressure settings to compensate for lower boiling temps. Always follow a tested table for your altitude.

14) Can you “modernize” family recipes that were used when people Stored Food Before Refrigerators?

Yes—by mapping flavors to tested modern recipes (for acidity, times, and headspace) while keeping spices and herbs as your creative space. Do not change vinegar strength, salt %, or processing times in tested formulas.

15) What’s the best starter method if you’re new to pre-fridge techniques?

Begin with vinegar pickles, basic jam, or a small sauerkraut crock. You’ll learn acidification, water-bath canning, or fermentation without specialized gear—and build confidence quickly.

16) How can you use these methods during power outages?

Have a plan: cook and pressure-can meats if safe time allows, quick-pickle perishable veg, dehydrate what you can, and lean on evaporative cooling for ultra-short term. Keep coolers and ice on hand as a bridge.

17) Why include the keyword “Stored Food Before Refrigerators” in your guide?

It helps readers find exactly this topic—historic methods adapted for modern safety—and signals that you’re covering strategies people used before refrigeration, with practical steps you can use now.

CTA & Product Recommendation

Ready to turn these methods into a working no-fridge pantry?

Build your shelf-stable plan with The Lost Superfoods →

Recommended Resources

The Lost Superfoods — step-by-step projects for dried/salted proteins, portable soup, rendered fats, hearty dry mixes, and more (modern safety adaptations).

The Self-Sufficient Backyard — layouts and checklists for root cellars, cool pantries, and small-space systems that support pre-refrigeration storage.

Old Wisdom, New Confidence

You don’t need a compressor to build food security—you need clear steps. Cool earth, salt, smoke, acid, sugar, and time still work when you pair them with tested recipes, measured brines, and correct processing. Start with one project—pickles, kraut, or a simple jam—then add a root bin or grain bucket next month. As you rotate, label, and refine, you’ll master how people Stored Food Before Refrigerators—safely, deliciously, and on your terms. Tell me what you’ll try first.

Pick one method—quick pickles, a small sauerkraut jar, or a root bin—and set it up today. Come back and share what you tried, what you learned, and which preservation skill you want to master next. Your experience helps other readers build better, smarter pantries.